The Drawings in the Cave of Altamira

In 1879, Maria Sanz de Sautuola, then 8 years old, accompanied her father, Marcelino, an amateur archaeologist, in exploring the Altamira caves in northern Spain. While her father carefully searched the ground for ancient tools, Maria, holding an oil lamp, looked up at the ceiling and exclaimed with amazement, "Father, look, bulls!".

The discovery met with skepticism in the scientific community. Many scientists refused to believe that prehistoric people could have created such perfect works of art. It took more than 20 years for the authenticity of the drawings to be recognized. Today, the Altamira cave, dating from a period between 35,000 and 11,000 years ago, is included in the UNESCO World Heritage list and is considered one of the greatest monuments of primitive art.

Underground Gallery from the Ice Age

On September 18, 1940, four French teenagers - Marcel Ravidat, Jacques Marsal, Georges Agnel, and Simon Coencas - were playing with their dog, named Robot, on a hill near the village of Montignac.At one point, the dog fell into a hole formed between the roots of a large tree. Trying to find a way to get him out, the boys discovered a narrow entrance. Armed with flashlights and a rope, they descended into the darkness and were the first people in 17,000 years to see the unique prehistoric drawings.

The cave's walls and ceilings were covered with hundreds of images: figures of bulls, deer, horses, and mysterious symbols. Particularly impressive was the "Hall of the Bulls" with large frescoes, up to five meters long.

The paints used by the ancient artists were made from natural minerals: ochre, hematite, and manganese oxide. The drawing technique proved so advanced that scientists had to revise their perceptions of human cultural development in the Paleolithic.

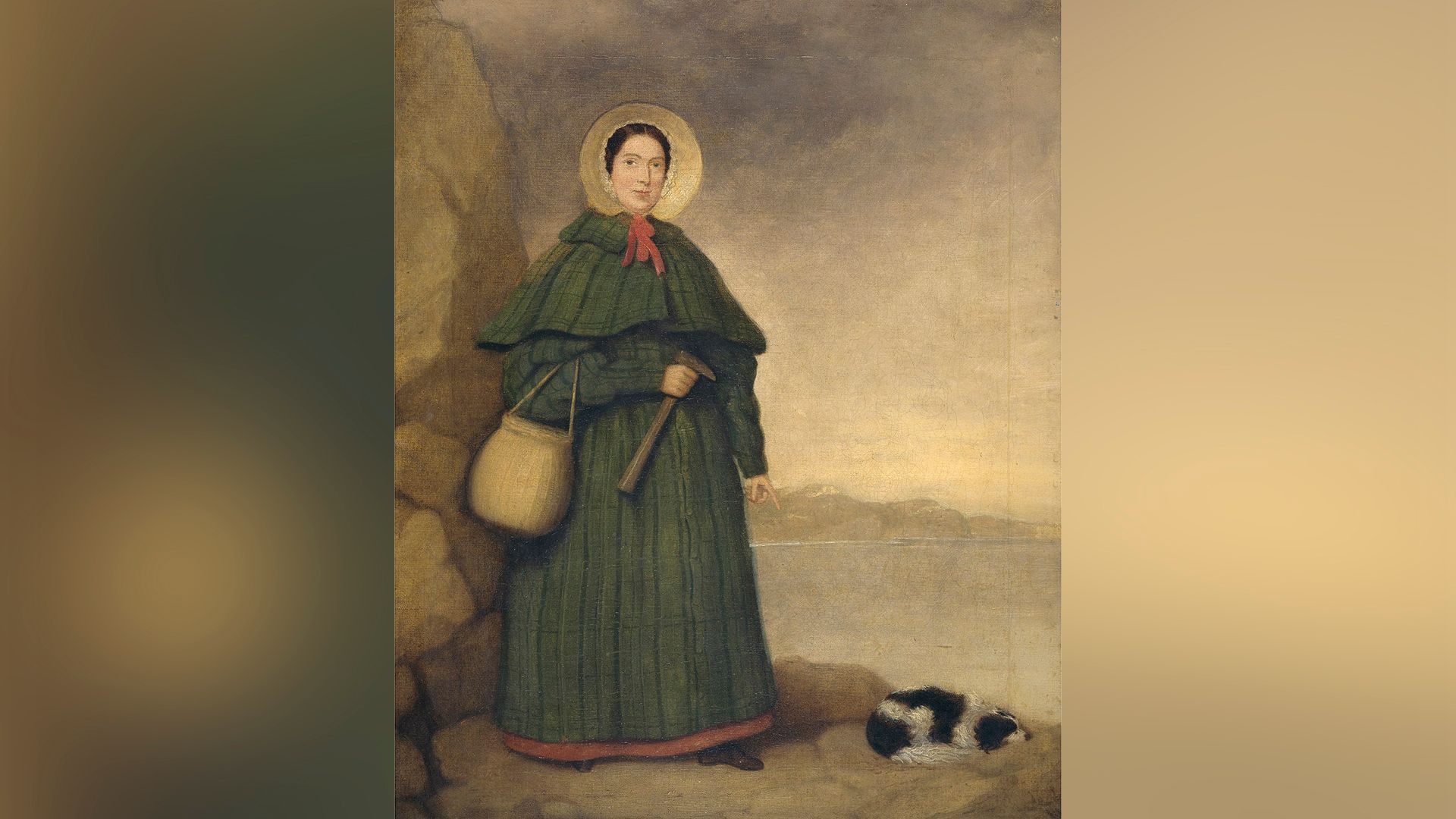

The First Complete Ichthyosaur Skeleton

In 1811, 12-year-old Mary Anning, along with her brother Joseph, were searching for fossils in the cliffs of Lyme Regis (Dorset, England) – their family was in great need, and the discoveries, mainly ammonites and belemnites, which were believed to have medicinal properties at the time, could be sold to tourists.The girl noticed an unusual fossil in the Jurassic shales (deposits from the Jurassic period). They turned out to be bones, but they did not resemble those of humans or animals. For several months, regardless of the weather, despite storms and tides, she meticulously unearthed the skeleton of a creature later named the ichthyosaur.

In the following years, Mary made many other important discoveries, including the first complete skeletons of the plesiosaur and pterosaur. Although women in Britain at that time did not have access to science, she became a recognized expert in paleontology, and her discoveries, now preserved in the world's largest museums, confirmed the hypothesis of dinosaur extinction.

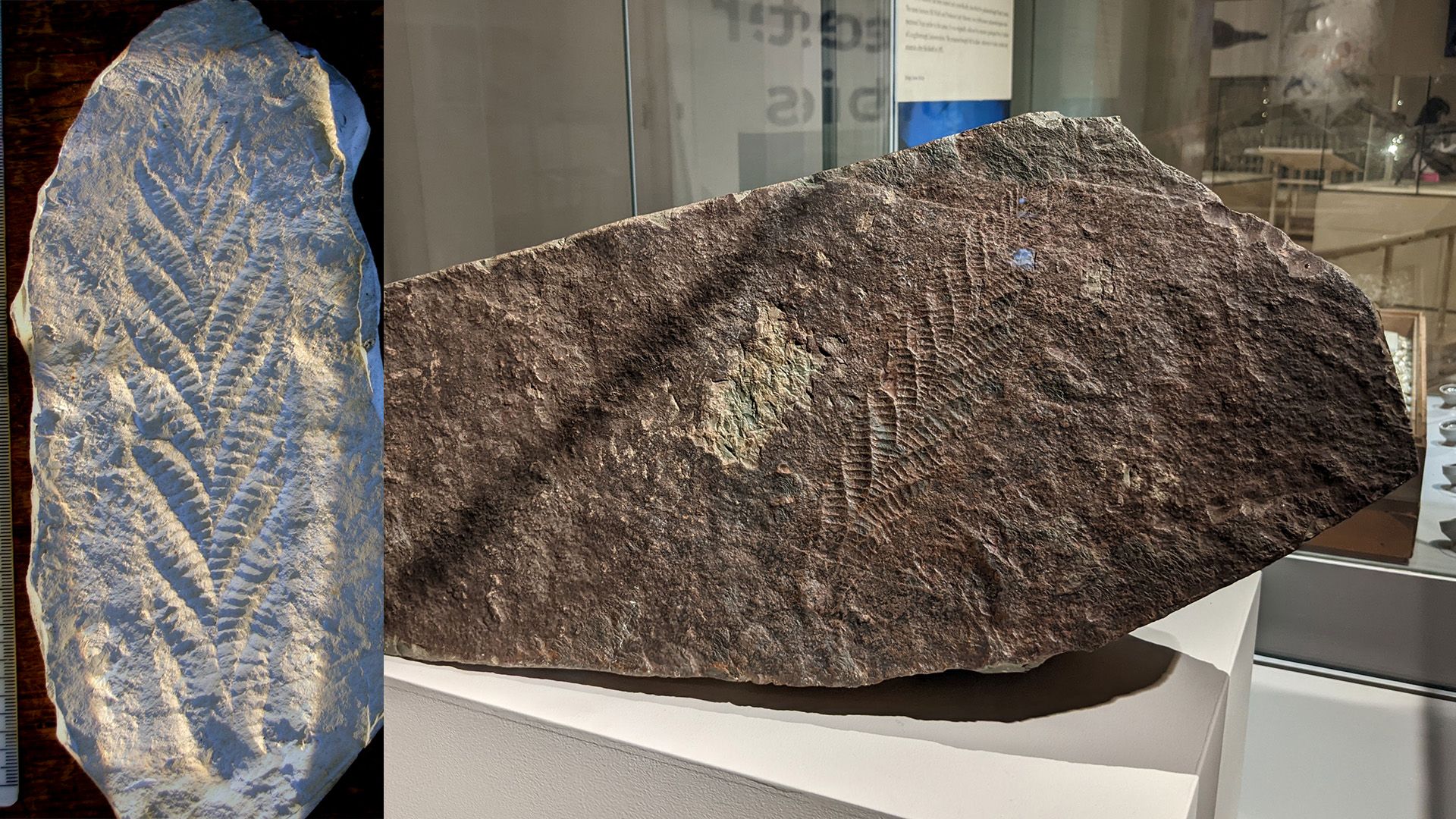

Charnia: A Unique Organism from the Precambrian Period

In April 1957, 15-year-old Roger Mason discovered a leaf-like imprint in the rock while climbing with his friends in Charnwood Forest, Leicestershire, UK. It turned out to be a fossil of the oldest multicellular organism from the Precambrian period, a time when life on Earth was just beginning to emerge.Due to its leaf-like shape, scientists initially thought the discovery was a fossilized plant. However, they later determined it was a representative of an extinct group of organisms called the Vendobionts (or Ediacaran biota) – some of the oldest known multicellular organisms.

The Explosion of a Supernova

In 2010, Catherine Aurora Gray, a 10-year-old Canadian girl, along with her father, an amateur astronomer, participated in a supernova search project as part of a program for young astronomers. While reviewing telescope images, she noticed a bright explosion in a galaxy located in the constellation Camelopardalis, approximately 240 million light-years from Earth.Professional astronomers confirmed that Catherine discovered a previously unknown Type Ia supernova—a powerful thermonuclear explosion occurring at the collapse of a white dwarf. The discovery was officially named SN 2010lt and added to the international catalog.

These stories show that great discoveries can be made not only by professional scientists but also by curious children. Their objective view of the world, sharp observation, and non-stereotypical thinking sometimes lead to discoveries that change our perception of history, science, and evolution. Perhaps the next big discovery will be made by another young researcher who just looks closely at the world around them.